ECONOMICS STUDY CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF DHAKA

|

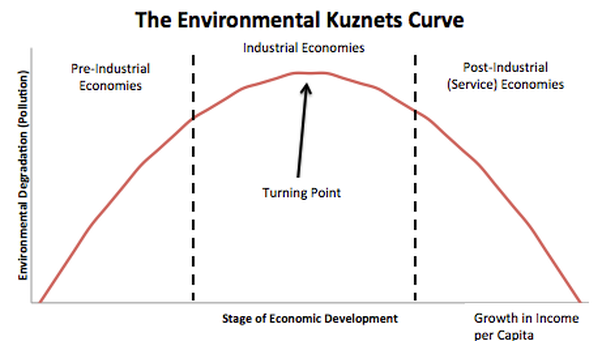

Namira Shameem Before we go on to celebrate even one-tenth percentage increase in economic growth, let us stop and think of what costs are we really climbing up the ladder? To put it bluntly, economic activities can degrade ecosystems. Since many of the ecosystem services (the benefits of ecosystems to humans) such as clean air, are public goods which are non-excludable and non-rival, stakeholders have little incentive to maintain them. In contrast, where ecosystem service does have a market value, such as fibre, economic activities may have environmental impacts that are not accounted for in the market price, also known as an environmental externality.  The dichotomy between increasing living standards by reaping the benefits of economic development, and preserving the ecology on which our future depends, is a challenge plaguing humanity since the Industrial Revolution. So while economic growth can inevitably harm the ecology, environmental policy is assumed to impede growth. Economic activities such as hunting, fishing or forestry which remove natural resources faster than they are able to replenish themselves threaten the very existence of such species, while agriculture is a source of water pollution as nitrates, cadmium etc. wash into the waters and pollute the aquatic ecosystem. Moreover, emissions such as carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide from the production of electricity, and other industrial sources pollute the air, making some cities in India, China, Iran the worst ones to dwell in. As population increases, so does the number of waste people produce. Plastic accounts for over 10% of the total waste we generate, and about 90% of all trash afloat on ocean surfaces. Its production and consumption are only increasing, with more than 1 million plastic bags used every minute, taking around 1 thousand years to degrade! Using disposable plastic that is non-biodegradable in exorbitant amounts is polluting our oceans, threatening aquatic life - killing 1 million seabirds and 100,000 marine mammals. Moreover, burning plastic leads to air pollution while disposing them at landfill sites leads to land pollution. Despite the general assumption that economically advanced nations tend to degrade the environment faster than poorer nations, the Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis says otherwise. According to the Environmental Kuznets Curve, as economic growth occurs and per capita income rises, the environmental quality will deteriorate till a specific point where the nation reaches a certain average income. After this, the nation is thought to invest back into the environment to remedy the damage. For example, when an economy is agrarian and pre-industrial, the level of pollution is minimal, but as it progresses towards development and industrialization, the risk of environmental pollution and depletion of natural resources increases, reaching a maximum. As the economy grows further and leans heavily on the tertiary sector, people choose to spend on improving their quality of life by adopting greener methods of living, and cleaner, more eco-friendly production facilities. In the United States, for example, research shows that although higher economic growth led to more use of cars, the levels of air pollution, especially sulphur dioxide levels, decreased significantly due to regulation. We have seen how environmental condition worsens as an economy develops. Now, let us look at whether the environmental policy can make more efficient use of scarce resources.

Some strategies for environmentally sustainable economic growth can be as follows: Internalising the externality: Often the people suffering the consequences of resource depletion and environmental degradation are those who play little role in its cause. For example, nitrogen fertilizers benefit crop production but the costs of eutrophication in surrounding waterbodies due to nitrate runoff is not borne by the users. Since fertilizer prices do not reflect these negative effects of fertilizer use, they do not impact people’s decisions about how much to buy or use. Some measures advocated by environmental economists to internalize externalities would be to include property rights and payments for use of environmental resources and accountability for environmental damage. Creating markets for ecosystem services: Markets such as these would act as incentives for environmentally safe investments and simultaneously compensate the unrelated parties for the actions benefitting the individuals involved. For example, people can invest in clean air in Beijing, similar to investing in other forms of security. These markets or projects must abide by certain “green standards”, and ensure regulation of land used, and protect biodiversity in the areas concerned. Improving predictive ability: Often, the environmental repercussions of economic activities are not apparent till it is too late. New modelling and forecasting tools can improve society’s capacity of predicting the highly uncertain anthropogenic changes in the ecosystem and its consequences. Routine risk assessment, monitoring systems to detect trends will help identify issues for society to address them in time. The above steps are only a few of the million we can take to strike a balance between economic growth and environmental protection. They ensure environmental policy fosters structural adjustments of the economy and encourage growth at the same time. Thus, in 2018, where we have only a little over a decade to attain the SDG goals of both economic growth and maintaining the environment/ecology, “green growth” is definitely the way to go!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Send your articles to: |